10 Friendly Everyday Objects With Dark Histories

SkyntCo Journal / Davit Petrosyan · 10/5/2025 · 8 min read

We love our cozy comforts: the cup that wakes us up, the toy that tucks us in, the little glam that makes us feel extra. But some of these cheery objects come with midnight stories—bans, curses, poisons, riots, and a newsroom cartoon that turned political brutality into plush. This isn’t about dusty antiques or ritual tools; it’s about items we still use, wear, sip, or step around every day. Consider this your friendly reminder that even the sweetest objects can carry shadows. Read on… if you dare look at your living room the same way again.

Pattern to watch: whenever a new thing rewires habit or taste, people panic, profiteers swarm, and unintended consequences follow. From moral panics to manufacturing shortcuts, the “dark” in these objects wasn’t magic—it was human.

10. Coffee — The “Devil’s Drink” That Got People Killed

Everyone’s favorite morning hug once had a serious PR problem. When coffee first seeped into Europe, some clergy branded the smoky, bitter brew “Satanic,” warning that the drink’s alertness and chatty coffeehouse culture could tempt people away from prayer. Legend says Pope Clement VIII tried a cup, loved it, and quipped that it would be a shame to leave the devil such a pleasure—effectively “baptizing” coffee into polite society.

Meanwhile, in seventeenth-century Istanbul, Sultan Murad IV treated coffeehouses as rumor factories and rebel incubators. Contemporary accounts claim he sent soldiers to smash cups, beat patrons, and even execute repeat offenders. Coffeehouses spread anyway, turning into engines of news and commerce—the original social networks no algorithm could throttle. Across centuries the same cup symbolized wickedness, heresy, revolution, and… productivity. It’s hard to imagine a more dramatic image shift for something we now queue for twice a day.

Sources: Smithsonian; Atlas Obscura.

9. Barbie — Born From a Grown-Up Gag Gift

Before she was a wholesome icon of pink convertibles and endless careers, Barbie’s family tree ran through a much spicier branch. In 1950s Germany, the Bild Lilli doll was a sassy, high-heeled novelty based on a newspaper cartoon—a joke gift for men, sold in bars and tobacconists. She smirked, she flirted, and she was never meant for kids. Mattel’s Ruth Handler reportedly encountered Lilli on a European trip, took notes, and returned to the U.S. with the blueprint for a very different future.

Barbie’s redesign softened the wink and turned the scandal into aspirational glamour; the risqué gag became a global childhood brand. Whatever you think of Barbie today—role model or unrealistic standard—her ancestor’s story proves that some of the world’s friendliest toys began life with a mischievous grin.

Sources: TIME; Science Museum Group Collection.

8. Teddy Bears — A Cute Toy From a Brutal Hunt

The cuddliest resident of the nursery owes its fame to a bleak scene in the woods. In 1902, during a Mississippi hunting trip, guides tied a captured black bear to a tree and urged President Theodore Roosevelt to take the shot. He refused, calling it unsporting—a sliver of mercy in a very ugly setup. The next day a Washington Post cartoon retold the incident, swapping gore for charm and depicting a sweet, frightened bear cub.

A Brooklyn shopkeeper saw an opportunity, stitched a plush, and asked to call it “Teddy’s bear.” Children embraced the toy; the gruesome context faded. It’s a classic American alchemy: transform a disturbing tableau into a comforting commodity—and then hug it to sleep every night.

Sources: Smithsonian (object record & history feature).

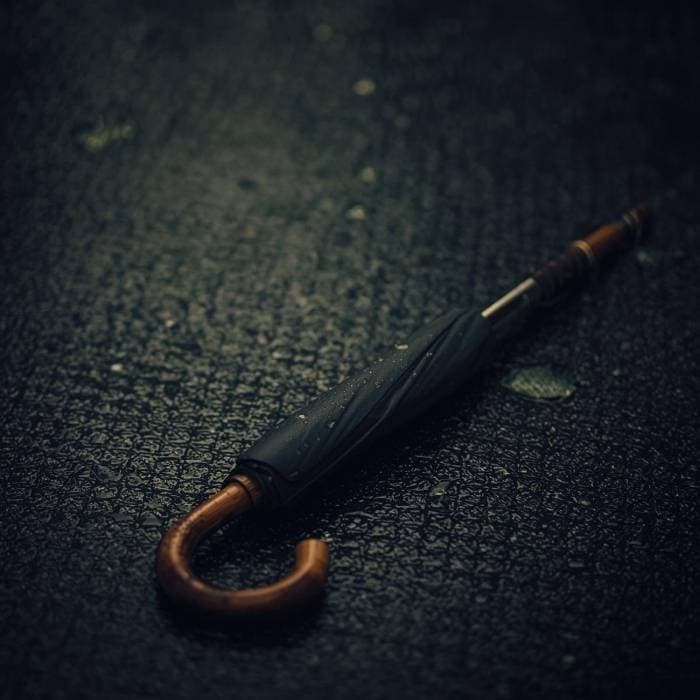

7. Umbrellas — London Once Tried to Bully Them Off the Streets

An umbrella seems like the politest invention imaginable, the opposite of road rage. Not in eighteenth-century London. Back then, many men considered umbrellas effete and un-English, a French affectation that threatened the income of coachmen who profited from rainy fares. When philanthropist and travel writer Jonas Hanway insisted on strolling under a brolly anyway, he became a mobile provocation.

Accounts describe passersby hurling insults, rubbish, even stones; coach drivers allegedly swerved or splashed him on purpose. Newspaper wit mocked the “macaroni” who hid from the weather like a dandy. The idea that a simple canopy once triggered a minor street war is absurd—and yet, it tracks. Technology that changes habits (and money flows) often meets ridicule before acceptance. Today no one bats an eye when you pop one open; in Hanway’s London, it marked you as a target.

Sources: Atlas Obscura; Londonist.

6. Balloons — From Animal Guts to Explosive Lab Tricks

Party balloons feel harmless, goofy, almost weightless—unless you trace their lineage. Long before latex, people inflated animal bladders and intestines for games and demonstrations. In 1824, chemist Michael Faraday introduced the first rubber balloons while experimenting with gases at London’s Royal Institution. He cut sheets of raw rubber, dusted them with flour to stop sticking, and filled them with hydrogen for demonstrations that could be as loud as they were enlightening.

In the decades that followed, novelty sellers borrowed the lab toy for parties, and the squeaky fun migrated from lecture hall to living room. The modern balloon is all smiles and helium giggles, but its ancestors belonged to the lab and the slaughterhouse. It’s hard to picture a balloon arch the same way after you imagine the squeak of stretched intestine.

Sources: Science World; Balloon HQ (historical FAQ).

5. Lipstick — Glam With a Side of Stigma (and Insects)

Lipstick’s history swings between taboo and power. In ancient Greece, certain crimson pigments signaled sex work by law; in later centuries, some formulas relied on dangerous compounds—think lead or mercury—that brought more than a rosy glow. The most brilliant reds came from cochineal, a beetle-based dye harvested by the millions.

In different eras, lawmakers tried to ban lipstick as deceit, churches scolded it as vanity, and monarchs embraced it as icon. Today a swipe can feel like armor, but the tube in your pocket is a reminder that beauty rituals have always balanced chemistry, culture, and controversy—with a few crushed insects along the way.

Source: National Geographic (history of red lipstick).

4. “Murder Bottles” — The Baby Feeders That Killed

Late-Victorian parents were promised a miracle: a long-tubed “self-feeding” nursing bottle you could prop beside the cradle, freeing hands and saving time. The design was a microbiological nightmare. Milk pooled in the rubber tubing, where scrubbing was nearly impossible; bacteria threw a banquet. Infant gut infections and deadly diarrhea followed.

Journal articles and public health campaigns blasted the devices, but they lingered in catalogs for years, some sold under the sunniest names. The nickname “murder bottle” wasn’t a moral panic—it was a grim statistic hiding in plain sight. Public pressure finally buried them—and saved countless babies who never knew the danger hovering by the crib.

Sources: Yale School of Medicine; UNMC Exhibit.

3. Mirrors — Pretty Portals With a Funeral Sheet

Mirrors have always felt a little too alive. Roman superstition warned that damaging your reflection meant seven years of misfortune—the time it took a soul to regenerate. In Jewish mourning, families traditionally drape mirrors during shiva to turn attention from appearance to remembrance; in folk belief, the covering also keeps spirits from disturbing the living or trapping the grieving gaze.

Elsewhere people told children not to look into mirrors at night or after a death in the home. Superstitions changed, but the instinct remained: treat the mirror as if something might be looking back. It’s just polished glass, we say. But our oldest stories treat it like a two-way threshold you should approach with respect.

Sources: University of South Carolina; ReformJudaism.org.

2. Glow-in-the-Dark Watch Dials — The “Radium Girls” Paid the Price

Early twentieth-century watch and instrument dials glowed a magical green thanks to radium-based paint. The workers who made them—young women employed by dial factories—were trained to lip-point their camel-hair brushes, twirling them between their lips for a fine tip. Each touch ingested radioactive dust. Radium settled in their bones, irradiating them from within; teeth fell out, jaws rotted, cancers bloomed.

Some workers painted their nails or teeth for fun at company parties, unaware of the risk; managers sometimes downplayed or denied the danger. The “Radium Girls” sued, won landmark settlements, and forced industry to adopt safety standards, but many died young. The next time you admire a vintage glow, remember the people who lit the way—and paid for it with their bodies.

Sources: Britannica; Science Museum Group; Library of Congress.

1. Poison Green Wallpaper — When Home Décor Could Kill

Victorians craved intense color, and Scheele’s Green (and later Paris Green) delivered—a jewel-tone pigment that popped on wallpaper, dresses, even toys. Unfortunately, those greens often contained arsenic. In damp rooms, the pigment could shed dust or react with mold, releasing toxins into the air.

Doctors warned families to strip the paper; satirical magazines mocked “fashion victims” literally being made sick by their décor. A persistent rumor even tags Napoleon’s exile bedroom, lined with green wallpaper, as a potential chronic source of exposure. Whether or not his case fits the chemistry, the broader story holds: an era’s most cheerful hue may have quietly poisoned its admirers—and it took decades of public health battles to put that fashion to rest.

Sources: Smithsonian; Maryland Center for History & Culture.

Closing: The next time your coffee steams, your lipstick gleams, or your watch glows—remember: friendly objects can have ghost stories. Happy (almost) Halloween. 🎃

- #history

- #culture

- #halloween

- #bizarre